LV: Hi Anh! Thank you for agreeing to this email interview. I was just looking at your website and I saw you have 4 children. You must be very busy! I have a two year old and it is a constant juggling act for me to be both an artist and a parent.

I would love to know more about how it is for you to be an artist and a parent. I see a wonderful tension in your work between stillness and movement and somehow it reminds me of being an artist and a mom-- having an hour of silence while the whole world rushes on.

AN: I constantly think about how to navigate parenting and sustaining an art practice. Not just painting time but also ‘percolation and interleaving’ (a nicely articulated term I heard from the British artist Sara Lee Roberts), which is really thinking time, but a kind of thinking that embraces interruptions, unexpected occurrences and distractions...The idea is that this allows your brain to switch off, refresh, and re-engage. So that when you do get that studio time (ie. nap times if your children nap!), it all comes out real quick! I also recall a quote (though unfortunately I can't attribute it!) where a female artist with children likened the time of intense parenting as preparation and practice, so that ‘when the time comes’, then one can travel as the arrow straight - true and direct.

I started my art practice during maternity leave with my 2nd child, about 5 years ago. I have described it in the past as a ‘catalyst’ of sorts. When I won the Basil Sellers in 2018, an interviewer asked a similar question, and my reply was something along the lines of not expecting painting to ‘save me’ - and this was met with a blank look, but now I think I can talk about it better. What I meant was that I don’t try and expect anything from my paintings, or rely on it to temper my mental and emotional state, nor do I wish to treat it as a kind of escapism. It is important to me to try and approach painting life as part of life, to be attuned to it - chaotic, hilarious, sad, weird, boring. And perhaps my paintings contain a sense of that, I’m not sure. I think approach is different to motivation. My motivation is more about visual experiences.

Another thing I’ve been thinking about in answering this question - that boredom has a lot to do with it, and it might explain why I am a relatively old emerging artist! I frankly don’t think I had it in me any earlier. I didn’t go to art school and I had more or less stopped painting in my 20s, though I still kept a visual diary of drawings and my own photography, and I watched a lot of movies in that period. Being a new mother reminds me in many ways of being a teenager at home in the suburbs again, with limited choices and mobility, and that you’d better get resourceful and imaginative very quickly, or how would you bear it. I feel my internal life and creative responses had an intensity to it then as when I started painting again as a parent.

LV: I love what you said about percolation and interleaving-- that is such a lovely image. Which leads me to my next question-- I'm curious about what you have to say about movement in your work. When I look at one of your pieces for a while I feel like I can sense the movement of time and also the movements of everyday life going on around you (like children running around). Do you work on your pieces at set times of day or do you include multiple times of day in one picture?

AN: It has changed depending on the ages of the children, what the daily activities are. When I first started my art practice, it was mostly commission work, so I would do that in the evenings. When I had little or no work, I started painting from life in the day time during naps. In the past, I think there was a kind of unconscious pressure on myself to complete paintings in one or two sittings, very intense high-stakes alla prima! Now I allow more slow paintings, over a period of time, and I use everything at my disposal - painting from life if it allows, painting from photographs and videorecordings, from invention and memory. There is no approach or method, except to take what is possible. So perhaps each time I return to a painting, I give it a little more energy, this movement you sense!

LV: Who/what has been inspiring you lately?

AN: I just received a copy of ‘Hockney on Art’, which I’ve never read before, and comes after reading his ‘Secret Knowledge’ last year. I am very interested in photography and what he talks about, the relationship between the mediums in terms of seeing and constructing a picture is really fascinating. I’ve just finished the chapter introducing what he calls ‘joiners’, which are like collage composites, ‘drawing with photography’, and I have started making my own responses to this with my iPhone and simple printouts.

LV: Those books sound great! I’ll add them to my list. I’m really curious about your collage cutouts. Any chance you would want to share some of them with me?

AN: Please find attached 5 joiners. Very basic but an interesting exercise in creating an account of many small moments without joining the lines that a panoramic or video eye would do. In the spirit of David Hockney’s approach, I did not alter or cut up the photos.

“Dancing w Doll”

“Opposite the Sea”

“Corner R & M”

“Driveway”

“Night Studio”

LV: These are great! They remind me of a talk by artist Elizabeth Flood who made some large paintings with several panels that included multiple horizon lines at different heights- she said this created a sense of being the viewer looking all around a scene (I don’t remember her exact words so I’m paraphrasing here). Have you found that making these joiners has influenced your painting practice?

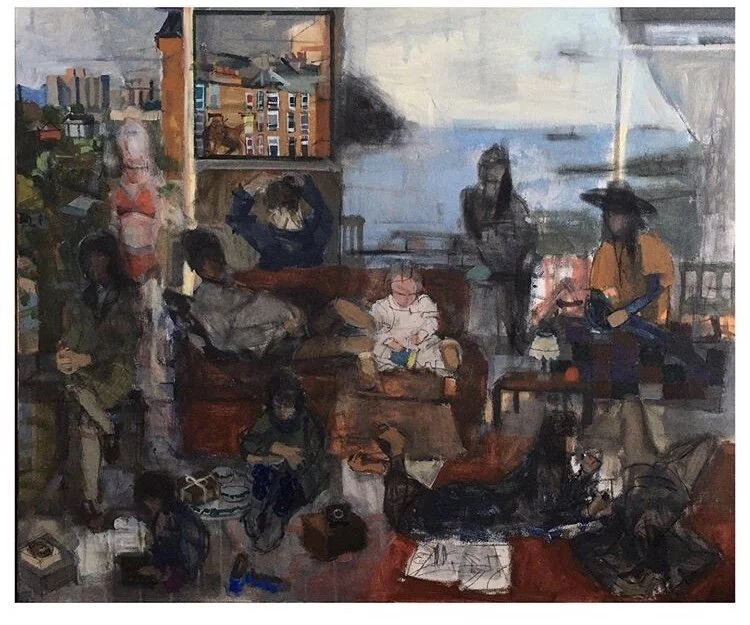

AN: It’s too early to tell of a direct influence I think! The Hockney book has prompted me to think more about looking in a more ‘cubist’ way certainly, that is, breaking from looking at something from a single viewpoint. The multiple horizons is a great example, it’s moving through the pictorial space because it forces you from standing still. I shared a painting a few months ago (below) where I had started thinking more about this, and I received a message later from another artist with the idea that multiple vanishing points can denote duration. That’s something to explore.

‘All of me’ (2020), 76x92cm, acrylic & charcoal on canvas

LV: It's true! My eye slows down a lot in looking at this picture! Okay so I’ll ask you one more question- how do you know when one of your pictures is complete?

AN: It’s finished when I’ve considered every bit of the surface and think it would simply be mucking around to do any more. Or I’ve lost interest. That’s ok to me to move on, I’m not after a perfect picture! Thank you for this very nice chat!!

LV: I keep thinking about something you said- that you’re not trying to make a perfect painting. So I’m curious what the inverse of that is- what kind of painting are you trying to make?

AN: It is so good to have these things to think about. :)

I'm not sure if it's the inverse, I think the painting process can be quite a perfect experience actually. In thinking about a response to your tricky question, I looked up the Latin meaning of "perfection"..."to finish" or "to bring to an end", but the origin of the concept apparently goes back to the Greeks, defining it as: complete (contains all the required parts, nothing to add or subtract), is good (nothing could be done better) and has attained its purpose.

Why not allow paintings to contain mistakes, bad decisions and unresolved areas? If we are self-conscious about technical ability or sloppiness, or repetition and unoriginality that's another matter. The kind of painting I want to make is serious about its motivation and intent for being made - why do I want to paint it and how? And thanks to the wise guy whoever said "A work of art is never finished, merely abandoned"!

LV: Thanks for your thoughts! I saw this post by Alex Kenevsky on facebook and it made me think of this question. What do you think?

Notes on Cy Twombly from the airplane over Great Plains.

as promised to Robert Bohné and anyone else who cares

Cy Twombly. I love the work this man did. Maybe I dont’ look in painting for something that many other people value. Academics look for theoretical underpinnings, intellectual games, semiotics, language theory, god knows what else, but it is always language based and outside of the art itself. Many look for political statements, expression of straggle: class, gender, race, environment, etc. Still others look for the evidence of superior skill worthy of admiration. I am just interested in painting as a form of visual poetry.

It seems to me that what the man attempted to do is the most difficult thing in art: he crated his own language that nobody other than himself knew and he wrote visual poetry in this language that was clear and transporting to anyone who would take the trouble to listen (or look).

The language of visual poetry, is direct and defenseless. It does not appeal to all. It does not appeal right away. It does not appeal for the reasons outside of itself. This often put this kind of art in and extremely vulnerable position with critics.

In his Doctor’s Notebooks William Carlos Williams tried to define what I am straggling to define here: how the true poetry is born. Williams worked as a pediatrician in the city hospital of Patterson, NJ. The population of Patterson was and still is largely immigrant. Many of the inhabitants speak very limited English. When coming to see the doctor they had to describe what was wrong with the children, fully understanding how important it was that the doctor understood. They often had to do that out of very limited vocabulary that they possessed. Try to speak clearly and eloquently about the things that are deadly important knowing only 200 words of the language that you must use. To Williams the parallel was clear: this is also how all real poetry is written.

This language that Cy Twombly developed seems childlike because it took what we find so compelling in children's’ drawings: simplicity, directness and vulnerability of means in order to express profound human drama. This can’t be faked. It is a difficult formal problem. Twombly attempted to solve it when he spent two weeks in a darkened garage unlearning his hand from anything it knew about drawing. He did hundreds of drawings by feel in this dark garage. Every time he felt his hand holding a pencil slipping into a familiar routine he would change something about the line: the pressure, the direction, the speed.

Because it is not about what it says in the word “Appolo", it is really more how it says this, how fast, how big, how careful or careless, what’s next to it, what’s hidden below it and what runs on the top. This syntax was developed in the dark garage, the greek myths were used more for their human rawness than for the metaphors contained in them.

If you accept this language as valid, suspend your habitual disbelief, the work begins to open up its formal sophisticated beauty. No real art is available to people who expect a sham. Don’t worry about being taken for a ride, don’t be too careful. Safety is not first. Put all your eggs in one basket. The outcome will be exhilarating one way or the other.

The direct emotional impact of this work never ceases to surprise me. Incidentally it is the same with the horribly wrong Cezanne’s bodies. Cezanne and Twombly made their choices. What mattered to them they wanted perfect. The rest of it they barely bothered with. This includes Cezanne’s anatomy and Twombly’s lack of interest in the modernist dogma. If you try to make everything perfect the work dies. If you focus only on things that matter to you and try to make only them perfect you might achieve something great, but it will leave you vulnerable to rapid judgements of the fearful and the suspicious.

AN: That was a great read - thanks! I like that train of thought actually, to aim to perfect only what matters to you. That’s good.

LV: Yes I agree! I used to almost only make one shot paintings and now I’m making paintings that take much longer- it’s been a rewarding and frustrating and rich experience. I ask about the idea of a perfect painting because I’m not really sure when my pictures could be done- they can go on and on and to so many interesting places.

AN: Ah, I see! Are you bothered by not being sure? Maybe if you perfect the thing that matters (or one or two or three but not everything in one picture?) - I think that thought is helpful. You can make lots and lots of paintings to discover all those things. :)